What is AI?

Think like humans

Cognitive science, cognitive modeling

Act like humans

The Turing Test:

- natural language processing,

- knowledge representation,

- automated reasoning,

- machine learning,

- vision,

- robotics.

Think rationally

Law of Thought Aristotle and other Greeks, logic Problem: representing knowledge, complexity

Act rationally

More general than the Laws of Thought Needs all the Turing Test requirements, plus Agents, etc.

Summary

Computational Rationality:

- Maximize Your Expected Utility

Foundation of AI

- Philosophy

- Mathematics

- Economics

- Neuroscience

- Psychology

- Computer Engineering

- Control Theory

- Linguistics

History of AI

-

1940-1950: Early days

-

1943: McCulloch & Pitts: Boolean circuit model of brain

-

1950: Turing’s “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”

-

1950—70: Excitement: Look, Ma, no hands!

-

1950s: Early AI programs, including Samuel’s checkers program, Newell & Simon’s Logic Theorist, Gelernter’s Geometry Engine

-

1956: Dartmouth meeting: “Artificial Intelligence” adopted

-

1965: Robinson’s complete algorithm for logical reasoning

-

1970—90: Knowledge-based approaches

-

1969—79: Early development of knowledge-based systems

-

1980—88: Expert systems industry booms

-

1988—93: Expert systems industry busts: “AI Winter”

-

1990—: Statistical approaches

-

Resurgence of probability, focus on uncertainty

-

General increase in technical depth

-

Agents and learning systems… “AI Spring”?

-

2000—: Where are we now?

State of the Art

- Robotics/Robotic Vehicles

Self-driving cars Soccer/Rescue…

- Natural Language Processing

Machine Translation Speech Recognition IBM Watson

- Autonomous Planning and Scheduling

Airline routing Factory pipeline

- Game Playing

Alpha Go Alpha Star

- Logistic Planning

Theorem Provers Betty’s Brain

- Vision

Object and face recognition Image classification

- Humanities

Education Healthcare

Agents & Environments

The Agent/Environment Architecture

Agents perceive their environments through sensors and act upon it through actuators

The environments outputs values that the agent perceives through its sensors

The values are passed to the agent’s agent function to decide how to respond

Upon a decision, the agent uses its actuators to execute the particular action

Agents and Environments

Agents perceive their environments through sensors and act upon it through actuators

Sensors

Sensors receive perceptual inputs from the environment

Actuators

Actuators allow the agent to then act upon the environment in some way

A self-cleaning agent perceives the neighboring tile is dirty A self-cleaning agent perceives the neighboring tile is dirty and acts to clean it

Percept Sequences

The complete history of everything the agent has perceived

An agent’s action can depend on the entire percept sequence to date

Agent Function

A mapping of actions to take for a given percept

| Percept | Action |

|---|---|

| [A1, CleanTile] | MOVE_RIGHT |

| [A1, DirtyTile] | CLEAN |

| [B1, CleanTile] | MOVE_LEFT |

| [B1, DirtyTile] | CLEAN |

| [A1, DirtyTile], [A1,CleanTile] | // Do Something |

We can expand this mapping to also store the complete history of percepts as well

Performance Measures

Evaluates any given sequence of environment states

No universal measure and dependent on the designer

Performance measures can be learned

If our cleaning robot’s performance measure was simply how many tiles it clean, what would a “smart” robot do?

Rational Agents

- Four considerations for rationality

- The performance measure

- The agent’s prior knowledge

- Possible actions

- The percept sequence available to the agent to date.

Rationality vs. Omniscience

Rational agents maximize expected outcomes, because we cannot account for everything

Rational Agent

For each possible percept sequence, a rational agent should select an action that is expected to maximize its performance measure, given the evidence provided by the percept sequence and whatever built-in knowledge the agent has.

- *P*erformance measure

- Knowledge of *E*nvironment

- Actions (*A*ctuators)

- Perceptions (*S*ensors)

PEAS: Specification of the task environment.

For example:

| Agent Type | Performance Measure | Environment | Actuators | Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxi Driver | Safe, fast, legal, comfortable trips that maximize profit | Roads, other traffic, pedestrians, customers | Steering, accelerator, brake, signal, horn, display | Cameras, sonar, speedometer, GPS, odometer, accelerometer, engine sensors, keyboard |

Properties of Task

Fully vs. Partially Observable

If the sensors give the agent a complete state of the environment, then it is completely observable

The agent may not sense everything, giving it a partially observable environment

Deterministic vs. Stochastic

The next state of the environment is completely determined by the current state and action of the agent If the environment is deterministic except for the actions of other agents, it is considered strategic

Episodic vs. Sequential

- Agent’s experience is divided into atomic “episodes” (or time steps)

- Each “episode” consists of the agent perceiving and then acting

- The choice of the action in each episode depends only on that episode alone

Static vs. Dynamic

- The environment is static is it does not change while the agent is thinking

- Solving a crossword puzzle

- The environment is semi-dynamic, if its state doesn’t change with time, but the agent’s performance score does

- Playing chess with a clock

Discrete vs. Continuous

- A limited number of clearly defined percepts and actions

- Checkers have a discrete environment

- Self-driving cars would be continuous

Known vs. Unknown

- The designer of the agent may/may not have knowledge about the environment makeup

- In the environment is unknown, the agent will need to know how it works to decide

- Different from observable and unobservable

Single vs Multi-agent

- Other agents can be competitive or cooperative

- Agents can also communicate with each other

- Should any single agent treat another agent as an agent or part of the environment?

AI Agents Programs

Designing Agent Programs

An agent program takes in just the current percepts instead of maintaining its entire history. This is because storing the entire history could grow very large and become difficult to traverse.

The agent program takes in the current percept of the environment from the sensors of the agent and returns an action to be performed by the actuators. If you need to depend on the entire percept sequence, the agent will have to remember the percepts.

To process video from a camera shooting at 30fps, 640x480, 24 bit color would grow exponentially

In a simple Table-driven Agent, a lookup table is used to match every possible percept sequence to the corresponding action. It is the most effective form of implementing the desired agent function, but it comes with a penalty of occupying humongous amounts of space. Even for a small game of chess requires 150th power of 10 entries in the lookup table, forget about the lookup table for the taxi driving agent(for comparison, the number of atoms in the observable universe is less than 80th power of 10). This huge requirement of space means that: 1) There is not much space in the entire universe to store this huge amount of data. 2) The designer will not have time to fill up the table. 3) Even if you make a learning agent to fill the lookup table on itself, it’ll take ages for it.

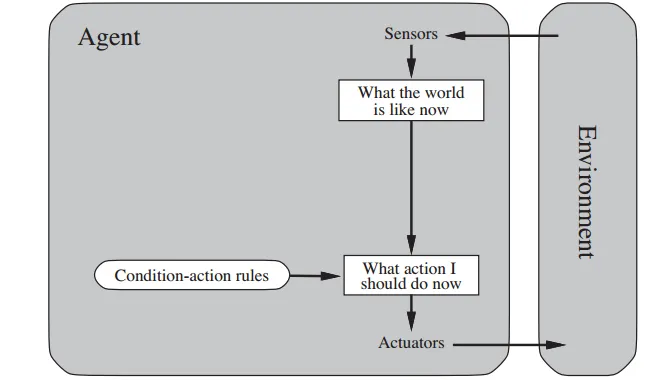

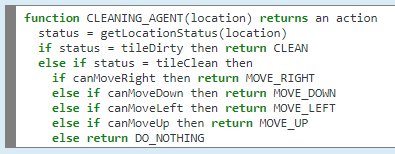

Simple Reflex Agents

- Select an action based on the current state and ignore the percept history

- Simple but limited

- Only work if the environment is fully observable

A simple condition-action rule governs the actions taken by the agent:

if condition, then action

Choose action based on current percept

Do not consider the future consequences of their actions

Consider how the world IS

def agent_func(Percept):

Rules = {"p0" : "a0", "p1" : "a3", ...}

Action = Rules[Percept]

return Actiondef agent_func(Percept):

Rules = {"p0" : ["a0", "a4", ...],

"p1" : ["a3", ...]}

Actions = Rules[Percept]

Choice = random.choice(Actions)

return ChoiceModel-based Agents

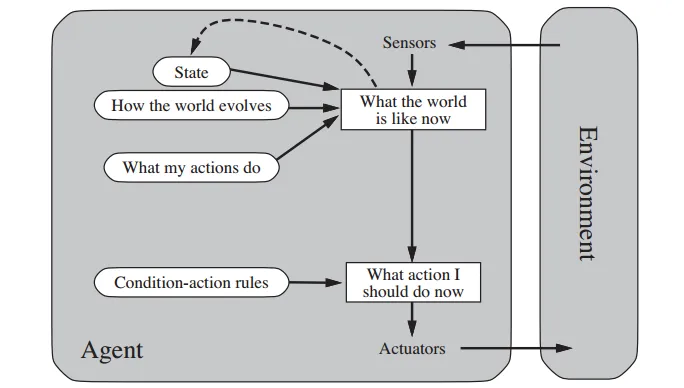

- Handle partial observability by tracking part of the world it cannot see.

- Internal state depends on the percept history (its best guess)

def agent_func(Percept, Curr_State, Last_Action):

Rules = {"s0" : "a0", "s1" : "a3", ...}

New_State = update_state(Curr_State, Last_Action,

Percept, Model. Action = Rules[New_State]

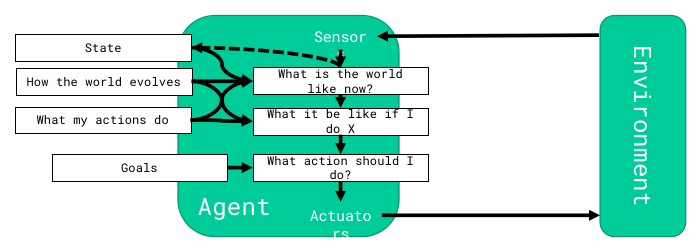

return (Action, New_State)Goal-based Agents

Knowing the environment is not enough, and needs a goal

- Combines goal and environment information to achieve that goal

def agent_func(Percept, Curr_State, Last_Action):

New_State = update_state(Curr_State, Last_Action, Percept, Model)

for Act in Possible_Actions:

Possible_State = check_act(New_State, Act)

if (Possible_State == Goal_State):

return (Act, New_State)Utility-based Agents

Goal isn’t enough to generate high-quality behavior in some of the environments, and so some addition utility is required

- This focuses on maximizing the goal by reducing costs

The performance measure should allow a comparison of the different states based on how “happy” the agent would be at that stage. This is defined as utility by the computer scientists. The utility-based agents maintains a utility function, which the agents try to maximize based on the external performance measure.

Utility, similar to defining a goal, is not the only way to be rational (we can’t define the utility function for a vacuum cleaning agent) but, like the goal-based agent, utility-based agent is flexible and adaptable to changing environments. Furthermore, utility-based agents can make rational decisions even when the goal-based agents fail to do so — this could happen in two cases: 1) When there are conflicting goals (safety vs speed in taxi-driving situation). 2) When there are multiple goals where none of them could be achieved with certainty. In both the cases, the utility-based agent specifies the appropriate trade-off (if the goals are conflicting), or the appropriate likelihood of success (if the goals are co-operative).

Utility-based agents fair well in partially observable environments, as it maximizes the expected utility to counteract the lack of observation. A reflex agent will also try to maximize the external performance measure based on the rules defined, but it doesn’t maintain an internal utility function to make up for the partial observability of the environment.

Learning Agents

Currently, in many fields of AI, the idea of how to initiate the agent (make the agent come into being) is solved by the technique of building the learning models and then training them, as proposed by Alan Turing (the great) in 1950. Learning also allows the agent to operate in initially unknown environments and to become more competent than its initial knowledge alone might allow.

-

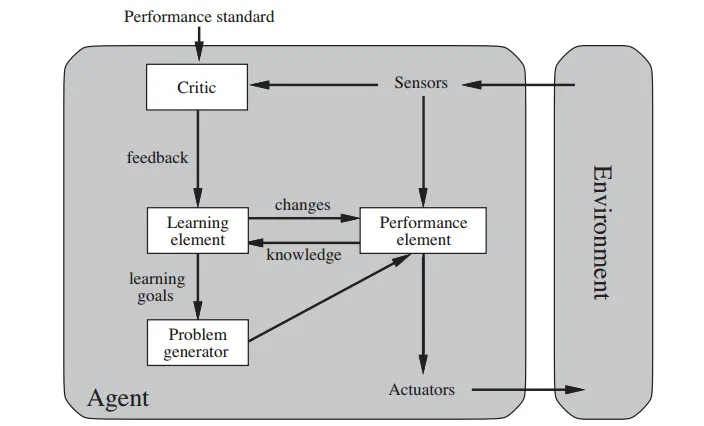

General Learning Agent

- Learning Element

- responsible for making improvements

- Performance Element

- responsible for selection actions

- Critic

- how well the agent is doing wrt performance standard

- Problem Generator

- allows the agent to explore

A learning agent can be divided into four conceptual components. The previously discussed agents comes under the performance element, which takes in percepts and returns actions. The learning element is responsible for modifying the behavior of the agent. It uses feedback from the critic on how the agent is doing and determines how the performance element should be modified to do better in the future.

The problem generator is responsible for suggesting actions that will lead to new and informative experiences. The performance measure commands the agent to do the best action, given what it knows of the current situation. But if the agent is willing to explore a little and do some perhaps suboptimal actions in the short run, it might discover much better actions for the long run.

The critic has to distinguish the performance standard from the percepts, and return a reward (or penalty) that provides a direct feedback on the performance of the agent. For example, Hard-wired performance standards such as pain and hunger in animals can be understood in this way.

Learning in intelligent agents can be summarized as the modification of agent’s behavior based on the available feedback information to improve the overall performance of the agent.

- Learning Element

AI agent frameworks

AI agent use case

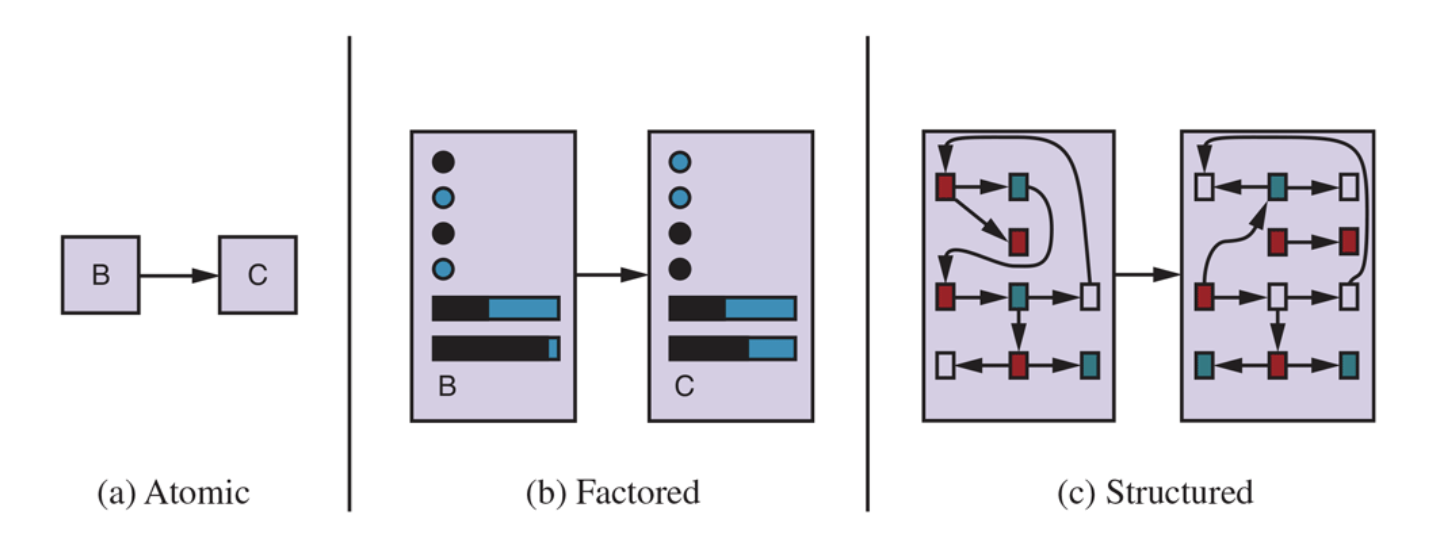

State Representations

Problem-Solving Agents

Planning Agents

- Ask “what if”

- Decisions based on (hypothesized) consequences of actions

- Must have a model of how the world evolves in response to actions

- Must formulate a goal (test)

Consider how the world WOULD BE

Optimal vs complete planning

Planning vs re-planning

Search Problems

difficult problems require searching More than one alternative needs to be explored The number of alternatives can be very large / infinite

Search space

The set of objects which we search for a solution

Goal condition

The characteristics of the object we want to find in the search space

Search

- The process of exploration of the search space

- Efficiency depends on

- Search space and its size

- Method used to explore/traverse

- Condition to test the satisfaction of the goal

- Goal formulation

- Limits the objectives the agent is trying to achieve

- Context

- Agent’s performance measure

- Problem formulation An abstraction of the real world

- State space

- Initial State

- Actions

- Transition model (successor function)

- Goal test

- Path cost

What’s in a State Space?

The world state includes every last detail of the environment

A search state keeps only the details needed for planning (abstraction) For example: Pacman Game

Problem: Pathing

States: (x,y) location

Actions: NSEW

Successor: update location only

Goal test: is (x,y)=ENDProblem: Eat-All-Dots

States: {(x,y), dot booleans}

Actions: NSEW

Successor: update location and possibly a dot boolean

Goal test: dots all falseState Space Sizes?

World state:

- Agent positions: 120

- Food count: 30

- Ghost positions: 12

- Agent facing: NSEW

How many

- World states? 120x(230)x(122)x4

- States for pathing? 120

- States for eat-all-dots? 120x(230)

Example Problems

Toy Problems

8-queen problem

- State space

- Initial State

- Actions

- Transition model (successor function)

- Goal test

- Path cost

8-Queen

- State space: Arrangement of the Queen’s on the board or a status of the board

- Initial State: It could be anything. Particular arrangement of the Queen’s on the board

- Actions: Placing one queen in a different place. Could move only one queen or all of queen

- Transition model (successor function): updated the location of the queens

- Goal test: Check whether the queen is attract with each other

- Path cost: how many steps you’re moving your queen. About your performance goals or performance measures

8 Puzzle

The N-Queen Problem

Given N queens on an N×N board, position the queens so no queen can attack another.

midtern 1

https://www.coursehero.com/sitemap/schools/1714-North-Carolina-State-University/courses/367271-CSC520/ https://www.coursehero.com/file/190939216/midterm1-2pdf/ https://www.coursehero.com/file/190939034/midterm1pdf/ https://www.coursehero.com/file/190938913/midterm1-20181217210415pdf/