Traits

Rust lets you abstract over types with traits. They’re similar to Interface:

trait Pet {

fn name(&self) -> String;

}

struct Dog {

name: String,

}

struct Cat;

impl Pet for Dog {

fn name(&self) -> String {

self.name.clone()

}

}

impl Pet for Cat {

fn name(&self) -> String {

String::from("The cat") // No name, cats won't respond to it anyway.

}

}

fn greet<P: Pet>(pet: &P) {

println!("Who's a cutie? {} is!", pet.name());

}

fn main() {

let fido = Dog { name: "Fido".into() };

greet(&fido);

let captain_floof = Cat;

greet(&captain_floof);

}Who's a cutie? Fido is!

Who's a cutie? The cat is!Trait Objects

Trait objects allow for values of different types, for instance in a collection:

trait Pet {

fn name(&self) -> String;

}

struct Dog {

name: String,

}

struct Cat;

impl Pet for Dog {

fn name(&self) -> String {

self.name.clone()

}

}

impl Pet for Cat {

fn name(&self) -> String {

String::from("The cat") // No name, cats won't respond to it anyway.

}

}

fn main() {

let pets: Vec<Box<dyn Pet>> = vec![

Box::new(Cat),

Box::new(Dog { name: String::from("Fido") }),

];

for pet in pets {

println!("Hello {}!", pet.name());

}

}Hello The cat!

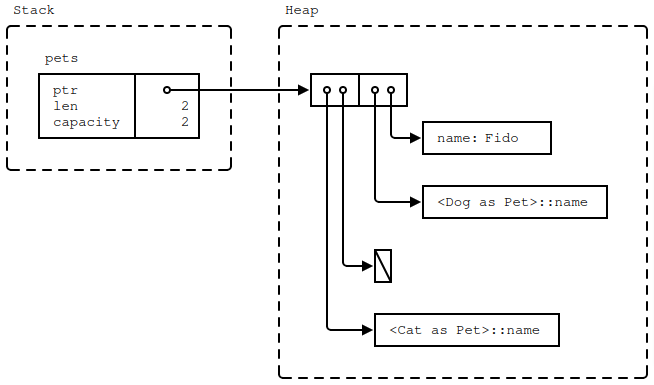

Hello Fido!Memory layout after allocating pets:

Notes

Notes

- Types that implement a given trait may be of different sizes. This makes it impossible to have things like Vec<Pet> in the example above.

- dyn Pet is a way to tell the compiler about a dynamically sized type that implements Pet.

- In the example, pets holds fat pointers to objects that implement Pet. The fat pointer consists of two components, a pointer to the actual object and a pointer to the virtual method table for the Pet implementation of that particular object.

- Compare these outputs in the above example:

println!("{} {}", std::mem::size_of::<Dog>(), std::mem::size_of::<Cat>()); println!("{} {}", std::mem::size_of::<&Dog>(), std::mem::size_of::<&Cat>()); println!("{}", std::mem::size_of::<&dyn Pet>()); println!("{}", std::mem::size_of::<Box<dyn Pet>>());

Deriving Traits

Rust derive macros work by automatically generating code that implements the specified traits for a data structure.

You can let the compiler derive a number of traits as follows:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq, Default)]

struct Player {

name: String,

strength: u8,

hit_points: u8,

}

fn main() {

let p1 = Player::default();

let p2 = p1.clone();

println!("Is {:?}\nequal to {:?}?\nThe answer is {}!", &p1, &p2,

if p1 == p2 { "yes" } else { "no" });

}Is Player { name: "", strength: 0, hit_points: 0 }

equal to Player { name: "", strength: 0, hit_points: 0 }?

The answer is yes!Default Methods

Traits can implement behavior in terms of other trait methods:

trait Equals {

fn equals(&self, other: &Self) -> bool;

fn not_equals(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

!self.equals(other)

}

}

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Centimeter(i16);

impl Equals for Centimeter {

fn equals(&self, other: &Centimeter) -> bool {

self.0 == other.0

}

}

fn main() {

let a = Centimeter(10);

let b = Centimeter(20);

println!("{a:?} equals {b:?}: {}", a.equals(&b));

println!("{a:?} not_equals {b:?}: {}", a.not_equals(&b));

}Centimeter(10) equals Centimeter(20): false

Centimeter(10) not_equals Centimeter(20): trueNotes:

-

Traits may specify pre-implemented (default) methods and methods that users are required to implement themselves. Methods with default implementations can rely on required methods.

-

Move method not_equals to a new trait NotEquals.

-

Make Equals a super trait for NotEquals.

trait NotEquals: Equals { fn not_equals(&self, other: &Self) -> bool { !self.equals(other) } } -

Provide a blanket implementation of NotEquals for Equals.

trait NotEquals { fn not_equals(&self, other: &Self) -> bool; } impl<T> NotEquals for T where T: Equals { fn not_equals(&self, other: &Self) -> bool { !self.equals(other) } }- With the blanket implementation, you no longer need Equals as a super trait for NotEqual.

Trait Bounds

When working with generics, you often want to require the types to implement some trait, so that you can call this trait’s methods.

You can do this with T: Trait or impl Trait:

fn duplicate<T: Clone>(a: T) -> (T, T) {

(a.clone(), a.clone())

}

// Syntactic sugar for:

// fn add_42_millions<T: Into<i32>>(x: T) -> i32 {

fn add_42_millions(x: impl Into<i32>) -> i32 {

x.into() + 42_000_000

}

// struct NotClonable;

fn main() {

let foo = String::from("foo");

let pair = duplicate(foo);

println!("{pair:?}");

let many = add_42_millions(42_i8);

println!("{many}");

let many_more = add_42_millions(10_000_000);

println!("{many_more}");

}("foo", "foo")

42000042

52000000Notes

- Show a where clause, students will encounter it when reading code.

fn duplicate<T>(a: T) -> (T, T)

where

T: Clone,

{

(a.clone(), a.clone())

}- It declutters the function signature if you have many parameters.

- It has additional features making it more powerful.

- If someone asks, the extra feature is that the type on the left of “:” can be arbitrary, like Option<T>.

impl Trait

Similar to trait bounds, an impl Trait syntax can be used in function arguments and return values:

use std::fmt::Display;

fn get_x(name: impl Display) -> impl Display {

format!("Hello {name}")

}

fn main() {

let x = get_x("foo");

println!("{x}");

}Hello fooimpl Trait allows you to work with types which you cannot name.

Notes The meaning of impl Trait is a bit different in the different positions.

-

For a parameter, impl Trait is like an anonymous generic parameter with a trait bound.

-

For a return type, it means that the return type is some concrete type that implements the trait, without naming the type. This can be useful when you don’t want to expose the concrete type in a public API.

Inference is hard in return position. A function returning impl Foo picks the concrete type it returns, without writing it out in the source. A function returning a generic type like collect<B>() → B can return any type satisfying B, and the caller may need to choose one, such as with let x: Vec<> = foo.collect() or with the turbofish, foo.collect::<Vec<>>().

This example is great, because it uses impl Display twice. It helps to explain that nothing here enforces that it is the same impl Display type. If we used a single T: Display, it would enforce the constraint that input T and return T type are the same type. It would not work for this particular function, as the type we expect as input is likely not what format! returns. If we wanted to do the same via : Display syntax, we’d need two independent generic parameters.