Ownership

All variable bindings have a scope where they are valid and it is an error to use a variable outside its scope:

struct Point(i32, i32);

fn main() {

{

let p = Point(3, 4);

println!("x: {}", p.0);

}

println!("y: {}", p.1);

}- At the end of the scope, the variable is dropped and the data is freed.

- A destructor can run here to free up resources.

- We say that the variable owns the value.

Move Semantics

An assignment will transfer ownership between variables:

fn main() {

let s1: String = String::from("Hello!");

let s2: String = s1;

println!("s2: {s2}");

// println!("s1: {s1}");

}s2: Hello!- The assignment of s1 to s2 transfers ownership.

- When s1 goes out of scope, nothing happens: it does not own anything.

- When s2 goes out of scope, the string data is freed.

- There is always exactly one variable binding which owns a value.

Notes

- Mention that this is the opposite of the defaults in C++, which copies by value unless you use std::move (and the move constructor is defined!).

- It is only the ownership that moves. Whether any machine code is generated to manipulate the data itself is a matter of optimization, and such copies are aggressively optimized away.

- Simple values (such as integers) can be marked Copy (see later slides).

- In Rust, clones are explicit (by using clone).

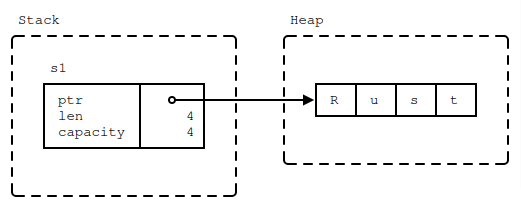

Moved Strings in Rust

fn main() {

let s1: String = String::from("Rust");

let s2: String = s1;

}- The heap data from s1 is reused for s2.

- When s1 goes out of scope, nothing happens (it has been moved from).

Before move to s2:

After move to s2:

After move to s2:

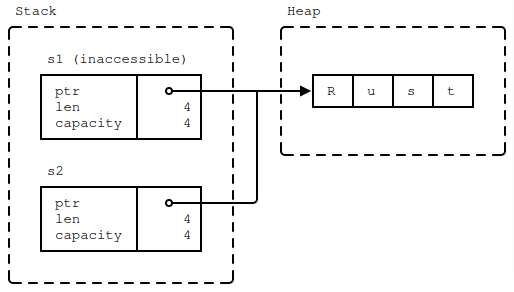

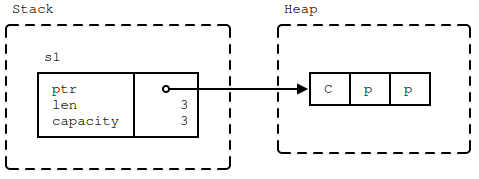

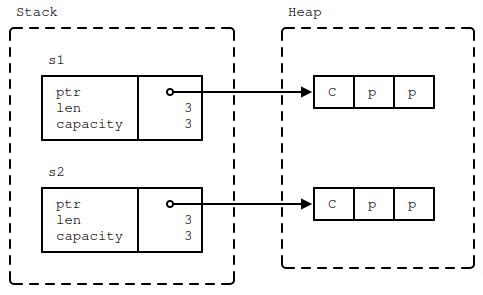

Extra Work in Modern C++

Modern C++ solves this differently:

std::string s1 = "Cpp";

std::string s2 = s1; // Duplicate the data in s1.- The heap data from s1 is duplicated and s2 gets its own independent copy.

- When s1 and s2 go out of scope, they each free their own memory.

Before copy-assignment:

After copy-assignment:

After copy-assignment:

Moves in Function Calls

When you pass a value to a function, the value is assigned to the function parameter. This transfers ownership:

fn say_hello(name: String) {

println!("Hello {name}")

}

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Alice");

say_hello(name);

// say_hello(name);

}Hello AliceNotes

- With the first call to say_hello, main gives up ownership of name. Afterwards, name cannot be used anymore within main.

- The heap memory allocated for name will be freed at the end of the say_hello function.

- main can retain ownership if it passes name as a reference (&name) and if say_hello accepts a reference as a parameter.

- Alternatively, main can pass a clone of name in the first call (name.clone()).

- Rust makes it harder than C++ to inadvertently create copies by making move semantics the default, and by forcing programmers to make clones explicit.

Copying and Cloning

While move semantics are the default, certain types are copied by default:

fn main() {

let x = 42;

let y = x;

println!("x: {x}");

println!("y: {y}");

}x: 42

y: 42These types implement the Copy trait.

You can opt-in your own types to use copy semantics:

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug)]

struct Point(i32, i32);

fn main() {

let p1 = Point(3, 4);

let p2 = p1;

println!("p1: {p1:?}");

println!("p2: {p2:?}");

}p1: Point(3, 4)

p2: Point(3, 4)- After the assignment, both p1 and p2 own their own data.

- We can also use p1.clone() to explicitly copy the data.

Notes Copying and cloning are not the same thing:

- Copying refers to bitwise copies of memory regions and does not work on arbitrary objects.

- Copying does not allow for custom logic (unlike copy constructors in C++).

- Cloning is a more general operation and also allows for custom behavior by implementing the Clone trait.

- Copying does not work on types that implement the Drop trait.

In the above example, try the following:

- Add a String field to struct Point. It will not compile because String is not a Copy type.

- Remove Copy from the derive attribute. The compiler error is now in the println! for p1.

- Show that it works if you clone p1 instead.

NOTE: about derive, it is sufficient to say that this is a way to generate code in Rust at compile time. In this case the default implementations of Copy and Clone traits are generated.

Borrowing

Instead of transferring ownership when calling a function, you can let a function borrow the value:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point(i32, i32);

fn add(p1: &Point, p2: &Point) -> Point {

Point(p1.0 + p2.0, p1.1 + p2.1)

}

fn main() {

let p1 = Point(3, 4);

let p2 = Point(10, 20);

let p3 = add(&p1, &p2);

println!("{p1:?} + {p2:?} = {p3:?}");

}Point(3, 4) + Point(10, 20) = Point(13, 24)- The add function borrows two points and returns a new point.

- The caller retains ownership of the inputs.

Notes on stack returns:

-

Demonstrate that the return from add is cheap because the compiler can eliminate the copy operation. Change the above code to print stack addresses. In the “DEBUG” optimization level, the addresses should change, while they stay the same when changing to the “RELEASE” setting:

#[derive(Debug)] struct Point(i32, i32); fn add(p1: &Point, p2: &Point) -> Point { let p = Point(p1.0 + p2.0, p1.1 + p2.1); println!("&p.0: {:p}", &p.0); p } pub fn main() { let p1 = Point(3, 4); let p2 = Point(10, 20); let p3 = add(&p1, &p2); println!("&p3.0: {:p}", &p3.0); println!("{p1:?} + {p2:?} = {p3:?}"); } -

The Rust compiler can do return value optimization (RVO).

-

In C++, copy elision has to be defined in the language specification because constructors can have side effects. In Rust, this is not an issue at all. If RVO did not happen, Rust will always perform a simple and efficient memcpy copy.

Shared and Unique Borrows

Rust puts constraints on the ways you can borrow values:

- You can have one or more &T values at any given time, or

- You can have exactly one &mut T value.

fn main() {

let mut a: i32 = 10;

let b: &i32 = &a;

{

let c: &mut i32 = &mut a;

*c = 20;

}

println!("a: {a}");

println!("b: {b}");

}Notes

- The above code does not compile because a is borrowed as mutable (through c) and as immutable (through b) at the same time.

- Move the println! statement for b before the scope that introduces c to make the code compile.

- After that change, the compiler realizes that b is only ever used before the new mutable borrow of a through c. This is a feature of the borrow checker called “non-lexical lifetimes”.

Lifetimes

A borrowed value has a lifetime:

- The lifetime can be implicit: add(p1: &Point, p2: &Point) → Point.

- Lifetimes can also be explicit: &‘a Point, &‘document str.

- Read &‘a Point as “a borrowed Point which is valid for at least the lifetime a”.

- Lifetimes are always inferred by the compiler: you cannot assign a lifetime yourself.

- Lifetime annotations create constraints; the compiler verifies that there is a valid solution.

- Lifetimes for function arguments and return values must be fully specified, but Rust allows lifetimes to be elided in most cases with a few simple rules.

Lifetimes in Function Calls

In addition to borrowing its arguments, a function can return a borrowed value:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point(i32, i32);

fn left_most<'a>(p1: &'a Point, p2: &'a Point) -> &'a Point {

if p1.0 < p2.0 { p1 } else { p2 }

}

fn main() {

let p1: Point = Point(10, 10);

let p2: Point = Point(20, 20);

let p3: &Point = left_most(&p1, &p2);

println!("left-most point: {:?}", p3);

}left-most point: Point(10, 10)- ‘a is a generic parameter, it is inferred by the compiler.

- Lifetimes start with ’ and ‘a is a typical default name.

- Read &‘a Point as “a borrowed Point which is valid for at least the lifetime a”.

- The at least part is important when parameters are in different scopes.

Notes In the above example, try the following:

-

Move the declaration of p2 and p3 into a new scope ({ … }), resulting in the following code:

#[derive(Debug)] struct Point(i32, i32); fn left_most<'a>(p1: &'a Point, p2: &'a Point) -> &'a Point { if p1.0 < p2.0 { p1 } else { p2 } } fn main() { let p1: Point = Point(10, 10); let p3: &Point; { let p2: Point = Point(20, 20); p3 = left_most(&p1, &p2); } println!("left-most point: {:?}", p3); }Note how this does not compile since p3 outlives p2.

-

Reset the workspace and change the function signature to fn left_most<‘a, ‘b>(p1: &‘a Point, p2: &‘a Point) → &‘b Point. This will not compile because the relationship between the lifetimes ‘a and ‘b is unclear.

-

Another way to explain it:

- Two references to two values are borrowed by a function and the function returns another reference.

- It must have come from one of those two inputs (or from a global variable).

- Which one is it? The compiler needs to know, so at the call site the returned reference is not used for longer than a variable from where the reference came from.

Lifetimes in Data Structures

If a data type stores borrowed data, it must be annotated with a lifetime:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Highlight<'doc>(&'doc str);

fn erase(text: String) {

println!("Bye {text}!");

}

fn main() {

let text = String::from("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.");

let fox = Highlight(&text[4..19]);

let dog = Highlight(&text[35..43]);

// erase(text);

println!("{fox:?}");

println!("{dog:?}");

}Highlight("quick brown fox")

Highlight("lazy dog")Notes

- In the above example, the annotation on Highlight enforces that the data underlying the contained &str lives at least as long as any instance of Highlight that uses that data.

- If text is consumed before the end of the lifetime of fox (or dog), the borrow checker throws an error.

- Types with borrowed data force users to hold on to the original data. This can be useful for creating lightweight views, but it generally makes them somewhat harder to use.

- When possible, make data structures own their data directly.

- Some structs with multiple references inside can have more than one lifetime annotation. This can be necessary if there is a need to describe lifetime relationships between the references themselves, in addition to the lifetime of the struct itself. Those are very advanced use cases.